This text was originally published in the Journal of Sublation Magazine and re-published in Italian language by MagIA.

(August 2024)

Fetishism

In his book “The Sublime Object of Ideology”, philosopher Slavoj Žižek unveils two distinct and seemingly incompatible modes of fetishism: commodity fetishism, which occurs in capitalist societies, and a fetishism of ‘relations between men,’ characteristic of pre-capitalist societies. Žižek’s analysis can be extended to incorporate a third—and most recent—mode of fetishism, namely, AI fetishism. We can locate AI fetishism as an ultimate symptom of Achievement Society, which, according to philosopher Byung-Chul Han, is ‘a society of fitness studios, office towers, banks, airports, shopping malls, and genetic laboratories.’

Everything, everywhere, all at once—the achievement society found itself in the midst of technological turbulence. A turbulence that leads to nausea for some and to esoterism for others. AI is everywhere: from smart home devices to algorithm-driven content recommendation systems; from biometric security measures to online shopping platforms; from finance, healthcare, public governance and mental health. (And, even in love too).

AI is libidinal technology. It has mobilised all the energies—emotions, desires, passions, affections—of corporate class, mainstream media, international institutions and governments. (And eugenics too). As a libidinal technology, we are told, AI will solve some of the world’s most pressing problems, create new inventions for humanity, and accelerate the economy, productivity, and well-being. It has evaporated some of the world’s harshest and complex problems and melted down into libidinal desiring-technology. Tellingly, AI produces a technological gaze, transforming human subjects into data points and algorithmic predictions, stripping away the complexity of human experiences and subjectivities, and reducing individuals to mere objects within a technological framework.

AI is a regime of perversion. For Lacan, what defines a pervert is not merely their actions but their occupation of a particular structural position in relation to the Other. The relationship of the governing and corporate classes with AI is perverse. Despite the risks, damages, and proven harms, AI continues to be promoted as inevitable. The narrative of inevitability is part of the ‘mechanism of disavowal’—a reaction to castration (recognised and ignored at the same time). This is exemplified in a tweet by European Commissioner, Therry Breton, who, while celebrating the approval of the EU AI Act, wrote: “We are regulating as little as possible — but as much as needed!” Isn’t this tweet an embodiment of the disavowal mechanism? In other words, we want to regulate AI as much as needed (so to say to ‘castrate it’), but as little as possible (hence the ‘disavowal’ as a reaction to castration). AI represents a technological fetishism. Similarly to how a fetish serves as a substitute for the maternal phallus following the boy’s perception of the female genital, as described by Freud, AI today serves as a substitute—in the form of a technological fix—for problems that are structurally political. Artificial neural networks (ANNs), one of the most dynamic aspects of AI and which power many of the AI systems today, are devoid of usability without human labour. They remain an infinite layer of interconnected nodes, or ‘neurons’, carrying empty weights in search of purpose. It is through human labour — sometimes provided for free, sometimes exploited in the peripheries of capital, or simply captured/stolen by private tech companies — involving data and knowledge production, labelling, annotating, training, and cleaning, that artificial neural networks (ANNs) gain their use-value. As the network learns from data during the training process, the neurons’ weights adjust, transforming the network into a tool of material use. The Silicon Valley lords have finally found their fetish, which they want to sell to everyone as a magical and supernatural power. AI – and particularly the competition to build the Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), a transhuman intelligence – has become the ulta-expensive fetish-toy and ritual pursued by the world’s richest people. This is evidenced by the recent reports stating that OpenAI’s chief scientist, Ilya Sutskever, has established itself as an esoteric “spiritual leader” cheering on the company’s efforts to realise AGI, collectively chanting “Feel AGI! Feel AGI!. While the new AI sect of Silicon Valley reaps the fruits of its fetish, this technological fetishism was built upon theft and exploitation.

Theftploitation

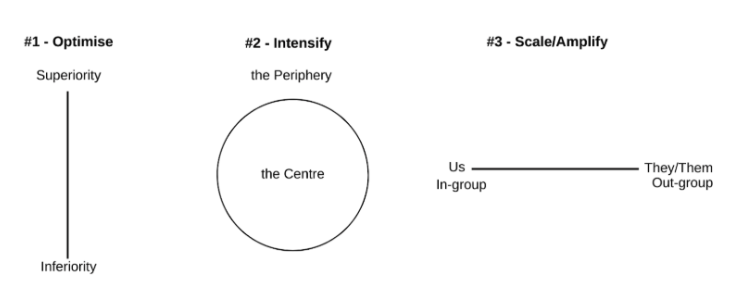

AI is built upon theft and exploitation. The convergence of theft and exploitation into the techno-political apparatus of AI is what I call theftploitation. Theftploitation represents the new, invisible mechanisms upon which AI is developed and maintained. All forms of exploitation that once were visible and solid in the disciplinary society have now dissolved into mathematical optimization and statistical correlations.

Let’s consider for a moment how the paradigmatic dataset known as ImageNet, which has enabled some of the best results in the development of ANNs, was built. Comprising more than 14 million labelled images, each tagged and categorised into more than 20,000 groups, ImageNet’s creation was made possible by the efforts of thousands of anonymous workers recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform. These invisible workers, who made ImageNet possible, were paid for each task they completed, sometimes receiving as little as a few cents. It is in the undemocratic relationship of domination between Center and Periphery, which dates back to the colonial and slavery periods, that we can locate the first mechanism of exploitation. With AI, plantations have dissolved into data-centres, slaves into ghost workers, masters into invisible algorithmic managers. All that was solid – capital, exploitation, and domination – has melted into the opaque techno-political apparatus of AI.

Many of the AI-powered services that we enjoy daily in the West—such as Google Maps, Airbnb, TripAdvisor, Uber, etc.—are maintained by the labour of thousands of invisible workers who are exploited on a daily basis. For most ordinary people, these services appear as simple conveniences, devoid of any underlying discord or exploitation. Here, we are confronted with what Lacan calls the Imaginary order: a world perceived as one of ease and connectivity, efficiency and productivity, mirroring a specular image of self-satisfaction that is devoid of the Real. Thus, in our daily interactions with these services, we engage not with the complex and often disturbing socio-economic realities—the Real—but with an Imaginary and the Symbolic orders that constructs the structure of our psyche in a manageable way; in other words, making the consumption of services feel effortless and friendly. However, according to Lacan, the Real must be apprehended in its experience of rupture, between perception and consciousness. The Real thus appears as a force of amorphous disruption which horrifies and disturbs, brutalises and overwhelms. But, instead of being perceived as a (political, economical) rupture, contemporary capitalism has facilitated the depoliticization of the public sphere and the creation of a post-political subject—a subject who, in Lacanian sense of jouissance (a deadly excess over pleasure), enjoys mobility and flexibility under the banner of ‘digital nomad’, ‘smart working’, and ‘flexible work’. This new class of workers, what Franco Berardi called the Cognitariat, is no longer disciplined by the Eye of the Master but is instead self-disciplined; it doesn’t suffer from physical exhaustion, but from mental burnout; and old-fashioned collective subjectivity is being replaced by hedonistic individuality’s ‘multitasking’. We can thus argue that the second type of exploitation is the self-exploitation of the achievement-subject who, according to Byong Chul-Han, ‘deems itself free, but in reality it is a slave’. Despite there being no master forcing the achievement-subject to work, writes Han, he or she exploits themselves without a master. The jouissance of the cognitariat is nothing else but what Lacan described as ‘perverted surplus-enjoyment’. Samo Tomšić’s interpretation of Marx and Lacan is remarkable in articulating the psyche’s mechanisms at play within capitalism, where, ‘the capitalist regime demands from everyone to become ideal masochists and the actual message of the superego’s induction is: ‘Enjoy your suffering, enjoy capitalism’.Finally, we come now to the third, and the last, mechanism of exploitation which takes the form of theft. In the PR debacle, OpenAI’s CTO, Mira Murati, was caught short of an argument when asked by a journalist which data was used to train Sora, OpenAI’s text-to-video generator. Initially, she responded by stating that they had used ‘publicly available data and licensed data.’ However, when the journalist further inquired whether they had used YouTube videos, Murati’s faltering response was accompanied by: ‘I am not actually sure about that.’ It has now become an open secret that tech giants have altered their own rules to train their AI systems by exploiting, capturing, appropriating and monetizing what Marx called the ‘general intellect’—the collective knowledge produced and published online in all its forms. Philosopher Slavoj Žižek has warned over a decade ago that:

the possibility of the privatisation of the general intellect was something Marx never envisaged in his writings about capitalism […]. Yet this is at the core of today’s struggles over intellectual property: as the role of the general intellect – based on collective knowledge and social co-operation – increases in post-industrial capitalism, so wealth accumulates out of all proportion to the labour expended in its production. The result is not, as Marx seems to have expected, the self-dissolution of capitalism, but the gradual transformation of the profit generated by the exploitation of labour into rent appropriated through the privatisation of knowledge.

AI represents a theft of global proportions. It has captured the creative work of artists, musicians, photographers, and the intellectual work of journalists, academics and scientists—not to mention the millions of volunteer hours spent worldwide by people contributing to platforms like Wikipedia—now presents itself as the future of humanity, albeit with a hefty price tag. Significantly, AI’s reach extends to natural resources as well. A recent publication by Estampa, a collective of programmers, filmmakers and researchers, illustrates how generative AI perpetuates the colonial matrix of power. It steals knowledge, exploits underpaid labour, and extracts natural resources such as land and water to sustain data centres, as well as raw materials required for the production of semiconductor chips, which are essential to enhance computing power and accelerate machine learning workloads.

Despite the large number of lawsuits against the major tech companies that have launched AI products, and the emergence of new forms of resistance such as data centre activism, there remains an open question: Will the AI industry be perceived as ‘too big to fail,’ similar to how banks were viewed during the 2008 financial crisis, and thus be preserved by existing judicial-political structures? If that is the case, who will pay the heaviest price?

We are at a pivotal moment where social, political, and economic arrangements are poised to enter into what Žižek called a ‘masochist contract’ with the big tech companies that own some of the main AI technologies and are taking over key public sectors such as education, healthcare, public administration, and so on. In the masochist contract, Žižek writes, it is not the Master-capitalist who pays the worker (to extract surplus value from him or her), but rather the victim who pays the Master-capitalist (in order for the Master to stage the performance which produces surplus-enjoyment in the victim). Consequently, we are going to witness the intensification of the politics of precarisation and austerity, exclusion and eviction, separation and marginalisation. We are going to see politics of brutalism administered by AI on behalf of two political rationalities: the radical centre and the far-right.

Brutalism

Brutalism, in architectural thought and practice, is intended as a style characterised by raw, cold, exposed concrete and bold geometric forms, often attributed to the French word ‘béton brut,’ meaning raw concrete. Brutalism perhaps represents what architect Alejandro Zaera Polo defines as the physicalization of the political. Emerging in the post-World War II period and with a strong positionality in Eastern Europe, brutalist architecture has been associated with socialist utopian ideas.

Invoking political aesthetics of brutalist architecture, philosopher and social critic Achille Mbembe, situates brutalism ‘at the point of juncture of materials, the immaterial, and corporeality’. For Mbembe, brutalism is ‘the process through which power as a geomorphic force is constituted, expressed, reconfigured, and reproduced through acts of fracturing and fissuring’, and its ultimate project is to ‘transform humanity into matter and energy’.

AI represents the ultimate form of the brutalist project. AI’s brutalism depends on three elements identified by Mbembe: materials, immaterial, and corporeal. AI’s dependence on materiality primarily revolves around the physical infrastructure required to develop, power, and maintain computation power for AI systems, including raw materials for hardware such as central, graphical, neural, and tensile processing units. Cloud infrastructure, as immaterial as it may sound, it’s not only material, but is also an ecological force with a greater carbon footprint than the airline industry. All that is solid, immaterial, and corporeal is melted into data-centres—these gigantic techno-architectural sites where physicalization of immateriality and corporeality is processed, and where social, political and economical relations are automatised. The immaterial aspects of AI are also crucial for its functioning. Some of the primary elements of human existence—our preferences, behaviours, interactions, desires, needs—are captured and used to feed ANNs. In return, we are presented with speculative offers for ‘personalised services’, in line with political rationality of neoliberalism; and with ‘predictions’, in line with political rationality of eugenics and far-right. As far as corporeality is concerned, AI today serves as a dispostif of power, to which both political rationalities–the radical centre and the radical right–are delegating their own dirty jobs.

A recent investigation by Israeli outlet +971 exemplifies AI brutalism—interactions among sufferers are classified as potential suspects with devastating material and corporeal effects. As one source stated in the investigation, ‘human personnel devote only about “20 seconds” to each target before authorising a bombing’. To put it in more Adornian terms, AI brutalism is the new administration method for violence, expulsion and eviction of the world’s most vulnerable groups. Even the newly-approved and highly-praised EU AI Act has (been criticised by human rights organisations for failing to properly ban some of the most dangerous uses of AI, including systems that enable biometric mass surveillance and predictive policing systems; as well as creating a separate regime for people migrating, seeking refuge, and/or living undocumented.

AI is the most contemporary form of this brutalism which, according to Mbembe, ‘does not function without the political economy of bodies’. Fanon, on the other hand, insightfully observes that ‘the economic substructure is also the superstructure; you are rich because you are white, you are white because you are rich.’ Therefore, racism hence is never casual, reminds us Fanon, and all forms of racism are underpinned by a structure. This structure serves what Fanon called a gigantic work of economic and biological subjugation (one can notice how we are again dealing with materiality and corporeality). A Fanonian reading of the EU AI Act suggests that AI obfuscates this structure by making it invisible, while simultaneously subjecting migrants and refugees to violent biopolitical tattooing practices such as: electronic fingerprint and retinal scanning, biometric voice recognition, AI-powered lie detector, etc.. AI thus becomes the Master-administrator of the borders as ‘ontological devices, namely, it now functions by itself and in itself, anonymously and impersonally, with its own laws’ (Mbembe 2024).

The borderization of Europe is not only marked by brutalist concrete walls and brutalist technologies such as AI; its core ideological tenets lie in the political rationalities of the radical centre and far-right. The first seeks bodies as “excesses” for extraction and monetisation (i.e. a form of surplus-life), while the latter sees them as “excesses” for expulsion and eviction (UK’s policy to organise mass deportation of asylum seekers in Rwanda, and Italy’s deal to outsource refugees in Albania are two most recent examples). The first envisages an AI-administered global technocratic regime, akin to the one echoed by Tony Blaire Institute, whereas the latter has already advanced in its hunt for biometrics. The first is the cause; the second is the consequence. We can think of the radical centre and far-right in a similar fashion to how generative adversarial networks (GANs)—a variant of reinforcement learning—function: one network attempts to fool another into believing that the data it generates actually originates from the training dataset. This approach has been used, for example, to create synthetic images of artworks and human faces that an image recognition system cannot distinguish from real images. Similarly, one political rationality tries to fool the other into believing that the politics and policies it generates reflects the genuine demands and needs of the populace. What in reality we get from both political rationalities are indistinguishably brutalist forms of techno-politics.

In the face of this dose of pessimism and deadlock, one should reorient oneself in line with Fanon’s concluding sentence in his essay “Concerning Violence”: ‘The European people must first decide to wake up and shake themselves, use their brains, and stop playing the stupid game of the Sleeping Beauty.’